Ryan McMaken – April 13, 2018

It was announced this week that the Denver Post will soon be cutting one-third of its newsroom staff. The newsroom currently has 100 reporters, and that will soon be cut by 30 positions.

Reporters and other observers quickly began to look for whom to blame.

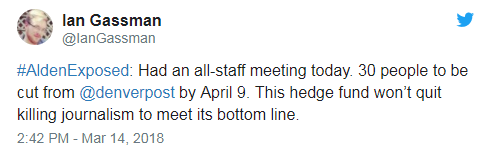

One reporter quickly blamed the hedge fund (Alden Global Capital) that owns the Post: ” 30 people to be cut from @denverpost by April 9. This hedge fund won’t quit killing journalism to meet its bottom line.”

This latest development comes mere weeks after the Denver Post announced it was erecting a pay wall around the site, no doubt in hopes of capturing more revenue.

At the time, one of the Post’s columnists blamed the readers themselves for the newspaper’s woes, implying that freeloaders were making it too difficult to deliver a media product and still keep the lights on. “We’re so over working for free,” the columnist concluded.

Well, now it appears that a third of the newsroom won’t be working at all since, apparently, the paywall isn’t bringing in as much revenue as hoped.

How Can Newspapers Stay in Business?

There is nothing unique about the Denver Post, of course. Old legacy newspapers across the country — from large shops like the Chicago Tribune to small ones like the Mt. Vernon Register-News — are laying off staff and sometimes even closing down completely.

(By “newspapers,” of course, I mean news organizations that once were based on selling physical newspapers. The business model of selling physical newspapers was abandoned years ago, though, so we’re speaking here of business models based on selling access to web-based news sources.)

So, what can newspapers do to stay in business and avoid layoffs?

The challenge for newspapers in this regard is no different than with any other market endeavor. In order to stay in business, firms must be able to offer consumers a product at a price that the consumer is willing to pay.

If consumers seem unwilling to pay for access to newspapers, this means the quality is perceived as being too low for the price demanded. The solution lies in either increasing the perceived quality, or reducing the price.

Recent studies have shown that many consumers — especially younger ones — are willing to pay for their news. In fact, the American Press Institute (API) concluded that “nearly 4 in 10 adults under age 35 are paying for news.” But here’s the rub: those who are still considering paying for news are price sensitive. The API’s surveys suggests consumers aren’t interested in paying more than one dollar per week (or 4-5 dollars per month) for their newspapers. Unfortunately for the newspapers, many of them are asking for more than double that rate. The Denver Post demands 12 dollars per month to get past the paywall. That’s even more than The New York Times, which charges eight dollars per month.

Both of these publications could overcome this problem by either convincing consumers that the product is worth more than a dollar per week. Or, the newspapers can find a way to reduce their production costs so that one dollar per week is sufficient to turn a profit.

Why Newspapers Are Unlikely to Provide What Consumers Want

It seems that many newspapers are unwilling to do this.

Indeed, there is an often-expressed sentiment among reporters, editors, and other newspaper staff that they are under-appreciated and that consumers should just be willing to pay more for access to newspapers. In other words, the belief among newspaper staff is “our quality is already fine, thank you very much. We perform an indispensable public service!” If the public is unwilling to see just how high the quality of newspaper work is, some seem to think, it just must be because the consumers are ignorant, prejudiced, or cheap.

Now, it is arguably true that, as newspaper industry people claim, some of the reporting done by newspapers benefits society as a whole. For example, investigative journalism that exposes government corruption has benefits beyond the mere reading enjoyment of subscribers. Even people who aren’t subscribers and never read the publications in question benefit from these activities.

But only a small portion of what newspapers do even qualifies under this “public service” umbrella. Most papers devote the lion’s share of effort to coverage of sports, movies, the local bar scene, and local ribbon cuttings. At the same time, reporters with no actual experience or qualifications in public policy, economics, or business, churn out columns in the opinion pages. None of this counts as a “public service.” Most of it is just entertainment or self-serving filler.

So, relying on the “public service” argument — and attempting to guilt people into paying more for newspapers — isn’t likely to pay the bills. As media scholar Clay Shirky has noted:

The newspaper people often note that newspapers benefit society as a whole. This is true, but irrelevant to the problem at hand; “You’re gonna miss us when we’re gone!” has never been much of a business model.

And this business model will become even more a failure as the competition for the public’s time, money, and attention intensifies.

This competition takes several forms. It comes from other media such as television, YouTube, and free online commentary on any number of topics from sports, to media, to politics. Newspapers also long ago lost the competition with organizations like Craigslist which made revenue-producing classified ads in newspapers obsolete. In other words, the quality of services offered by newspapers is not perceived as high enough to draw consumers away from the competition.

In most industries, entrepreneurs and firms will respond to new competition by attempting to offer a better product at a competitive price. And by “better” I mean something that the consumers are more likely to want. But that’s not how they roll in the newspaper industry. Rather than find a new business model that might entice readers back to where they might be willing to pay more for content, the main strategy of the newspapers, it seems, has been to blame their customers for being ungrateful.

It’s this lofty attitude about providing virtuous public service that leads many reporters to claim that it’s the job of newspaper owners to “quit killing journalism” when the owners demand that newspaper turn a sufficiently large profit. It’s this attitude that leads reports to complain about how reporters are “underpaid” instead of simply asking “what can we do to convince people to pay us more?” According to this way of thinking, everyone should be willing to make sacrifices — whether in the form of less profit or too-high prices — to keep the newspapers in business.

Why People Don’t Want to Pay More for News

As much as reporters might fancy themselves the voice of the people against the powers that be, the fact is that few people trust reporters, or see them as reliable sources of information. It’s likely even fewer see reporters as tribunes of the people. After all, according to Politico, only 7 percent of reporters identify as Republican. Four times as many identify as Democrats. Meanwhile, 37 percent of Americans overall identify as Republicans. While Party affiliation is not a reliable guide on one’s position on every issue, the general situation is nevertheless clear. It’s no wonder that during and after the 2016 presidential campaign, journalists seemed to regard Trump voters as bizarre eccentrics at best, and as violent extremists at worst. And “the people” appear to have picked up on this. According to Gallup, trust in the media in 2016 dropped to an all-time low, with only 32 percent of those polled saying they have trust and confidence in the mass media “to report the news fully, accurately and fairly.”

Moreover, in recent years, the journalistic standard of “objectivity,” always something of a fantasy in practice, has fallen away even as an ideal, as Sharyl Attkisson at The Hill writes:

Firewalls that once strictly separated news from opinion have been replaced by hopelessly blurred lines. Once-forbidden practices such as editorializing within straight news reports, and the inclusion of opinions as if fact, are not only tolerated; they’re encouraged.

Given this reality, it’s not difficult to see why many news outlets are having such a hard time convincing a large part of their audience to fork over cold, hard cash. If the customers think they’re going to be treated with contempt, they’re unlikely to want to pay for the newspapers’ end product.

Without a fundamental change in how newspapers and reporters see themselves, it’s hard to see how they’ll overcome the problem of high prices and perceptions of low quality. As with all successful market enterprises, the answer lies in providing a product the consumer is willing to pay for. But for now, all the evidence suggests that newspapers just aren’t very good at that.

This article was originally published at Mises.org. Ryan McMaken is an economist, and the editor of Mises Wire and The Austrian.