Chris Calton – October 19, 2022

In my second article on the college problem, I discussed the public policy factors that contribute to the rising cost of higher education. But politics makes its way into education through more than public policy, as professors bring their political views into their classrooms and research. Nothing has contributed more to my personal disillusionment with higher education than seeing the extent to which the ideological problem has affected the university system.

At the outset, let me say that the problem is not that professors have the wrong worldview. Some of the best and most impartial professors I’ve learned from have been on the left side of the political spectrum. Murray Rothbard approvingly cited Marxist and otherwise far-left historians, such as Eugene Genovese and Gabriel Kolko, in his own history works. The problem is that academia has become increasingly homogenous in its political outlook.

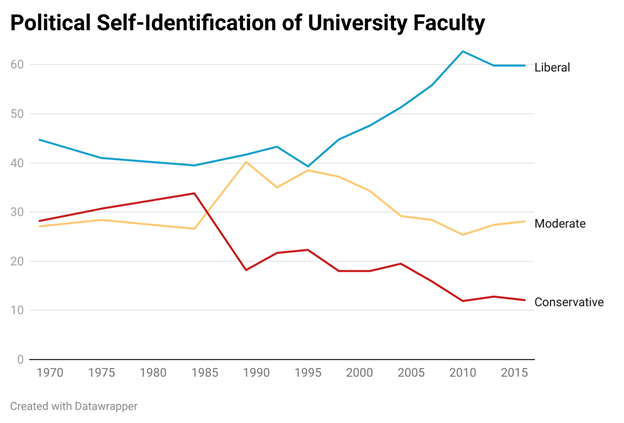

For better or worse, academia has always been disproportionately left of center, but in the last three decades, the skew has only become more pronounced. According to political self-reporting surveys of university faculty members, academics identifying left of center have increased by twenty percentage points since 1995, while self-described moderates and conservatives have correspondingly fallen. As of 2016, conservative professors accounted for barely 10 percent of university faculty, and the number has likely only fallen further since the survey was conducted.((Carnegie Commission Survey, 1969–1984; HERI Faculty Survey, 1989–2016.))

The problem is even more acute in the humanities and social sciences, not only in the proportion of left-of-center professors, but also in those reporting to be “far left.” One 2007 study found that 43 percent of social science and humanities professors identified as “radical,” “activist,” or “Marxist.”

The issue isn’t that left-wing professors are more prone to bias than their right-wing counterparts. In fact, a recent study has shown that the “willingness to discriminate” against opposing political views in publishing, symposiums, grants, and hiring is similar between left- and right-wing faculty members. However, a roughly equal “willingness to discriminate” means little when one side overwhelmingly outnumbers the other.

Ideological homogeneity leads to nepotistic hiring and admissions practices, which proves self-reinforcing as professors increasingly hire like-minded faculty members, who then go on to support further hiring of like-minded faculty in the future. This also affects admission to graduate programs. The 2016 book Inside Graduate Admissions, by Julie Posselt, examined the gatekeeping practices in the graduate admissions committees for several high-ranking universities. She found that committees showed clear biases against students with Christian and right-wing backgrounds.

It is worth understanding that rarely does this come in the form of a faculty member overtly expressing any objection to admitting or hiring candidates with “undesirable” political or religious viewpoints. Rather, it often comes with some “honorable” justification.

I recall having a conversation on this topic with a political science professor at the University of Florida. When I raised the subject of political nepotism in graduate admissions, she offered an example from her own department to illustrate that there may be good reasons to decline applications. She told me of a student who applied to the PhD program to study Israeli-Palestinian relations and seemed to have generally favorable views toward Israel.

The department rejected her application, I was informed, because they worried she might “feel uncomfortable” working with faculty who tended to be more critical of Israel. My first thought was What are these professors doing to make students so scared to disagree with them? Somehow this was meant to illustrate how the admissions process was not politically biased, despite the applicant’s political views being the explicit basis for refusing to admit her!

I should add that the professor who told me this story was generally moderate and never displayed any bias during my time in her seminar, and I have tremendous respect for her as an educator. But that’s exactly the point. Biases are rarely embraced consciously, and they often come with ostensibly noble reasoning. It hardly seems to occur to these faculty members that every department in the country might object to the candidate on the same grounds, creating industry-wide barriers to entering a graduate program for some students.

The homogeneity of faculty affects the undergraduate classroom experience as well. It is worth noting that although more than 70 percent of students report a reluctance to share their political or social views in the classroom, the general trend affects conservative students only slightly more than their left-wing counterparts. However, conservative students overwhelmingly cite fear of reprisal from professors as the source of their restraint. Students on the left, by contrast, generally fear ridicule and even violence from their peers, which seems to show the effects of the politicized caricature professors paint of conservatives in general; student surveys show that “students identifying as ‘extremely liberal’” were twice as likely to find violence “acceptable” to prevent campus speakers than “extremely conservative” students, likely due to the greater faculty support that left-wing students enjoy.

Finally, ideological homogeneity contributes to the breakdown of the peer-review process for scholarly publications. Again, this is not necessarily a conscious bias, as confirmation bias generally manifests through the comparative lack of scrutiny applied to claims that support people’s predispositions, regardless of their political leanings. The problem is that when the majority of reviewers share the same biases as the author, low-quality research that presents a majority view is more likely to reach publication than better-quality research that offers a contrary perspective.

The confirmation-bias problem in scholarly publications was recently exposed by the infamous “grievance studies” professors, who submitted satirical articles that were overwhelmingly polemical but appealed to the general biases of the academic community. These articles were deliberately designed to be unpublishable by conventional standards of academic rigor, with fabricated citations and absurd analyses, to test whether adopting the approved biases would be sufficient to get bad scholarship published. One article, which was published in the feminist journal Affilia, actually rewrote portions of Adolph Hitler’s Mein Kampf with postmodernist jargon, essentially testing whether Hitler would be able to earn tenure in the modern American academic climate. The answer, sadly, seems to be yes.

Of course, the bias in academia not only allowed several of these articles to be published, but it also directed the backlash against the authors once they admitted the hoax. Instead of opening a discussion about the failures of the peer-review system that the faux articles exposed, the academic community overwhelmingly excoriated the pranksters for committing academic fraud. Even for those who agree that the method of exposing the problem was inappropriate, the success of the hoax should have opened discussion on the problems that allowed these articles to be published in the first place, but this did not occur. Instead, the grievance studies professors, who were all left of center but sincerely cared about academic integrity, were ostracized by their peers, and some have been driven to resign from their teaching positions.

The purpose of higher education is to further the production (research) and distribution (teaching) of knowledge, but ideological homogeneity has led to the foiling of both purposes. The fact that this problem has manifested on the left side of the political spectrum in the United States does not mean that it would not be equally problematic if the ratios were reversed. Human beings are naturally prone to these kinds of biases, and the only way to check them institutionally is to promote political diversity in academia.

If academia were equally split between left- and right-wing faculty, professors would have to be more mindful of the impartiality of their analyses when submitting research for publication, and students would be exposed to a variety of viewpoints and enjoy a more open educational experience overall. Ironically, this is the only kind of diversity that seems to be negatively valued in universities today.

One way to change this is to encourage university donors to stop giving money to colleges that do not practice these values. This was essentially what happened during the similarly polemical environment of the 1970s, which compelled universities to crack down on political biases among faculty. The outcome was a less hostile and more apolitical campus environment in the 1980s and 1990s. Unfortunately, many donors who attended college in this era are unaware of how far academia has fallen in the past three decades, and they continue to financially support a broken system. Recognizing the scope of the problem is the first step toward solving it.

Originally published at Mises.org.

Image source: Adobe Stock