Ryan McMaken – May 26, 2022

In response to the Robb Elementary School shooting in Texas this week, one now sees repeated claims that school shootings are somehow “normal” or common in the United States.

For example, social media at this moment is teeming with users—assuming they’re not bots—posting about how they’re absolutely terrified of the idea of allowing their children to attend school. Yesterday, in a now deleted post, Elizabeth Bruenig—notable for writing on the topic of millennials having babies—declared that one reason millennials don’t have babies is because they believe their children are likely to be killed in a school shooting. Bruenig compared sending children to school to a sort of “lottery” system in which your child’s time to be killed in a shooting may come up at any time.

Some Europeans were eager to get in on the action also. El País, one of Spain’s largest dailies, presented “school shootings as a US norm.”

This is a pretty odd claim, however, given that school shootings are so rare that in the United States in 2021 there was one school-shooting death for every twenty-three million Americans. By comparison, approximately one in 350,000 Americans drowns each year.

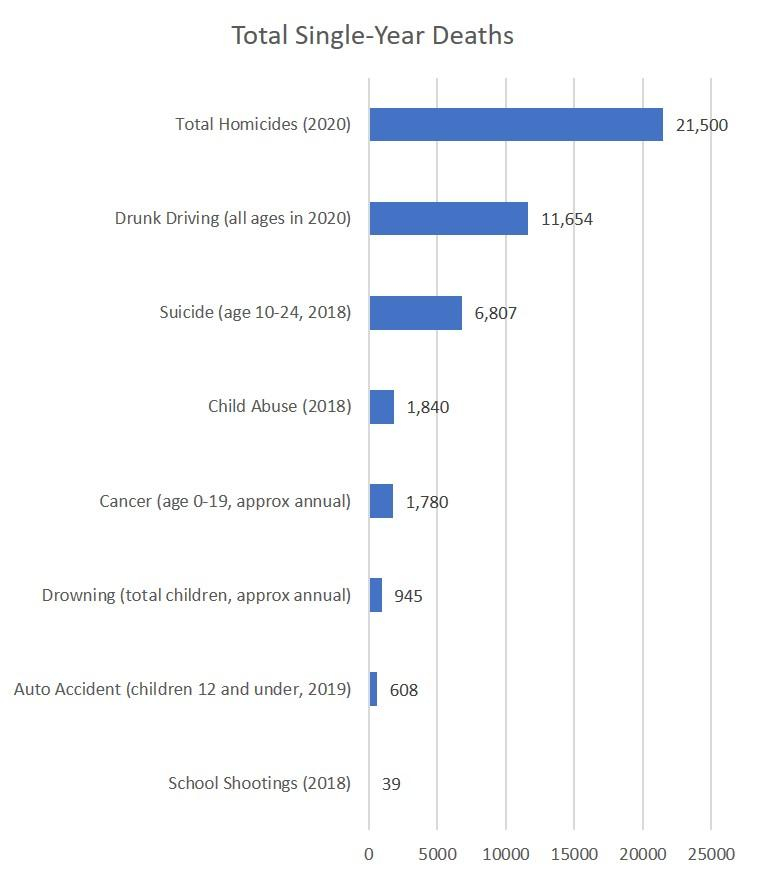

If one is going to be “terrified” of the dangers one’s children face, obsessing over school shootings is a rather odd thing to focus on. Our children are far, far more likely to be killed in an automobile accident than in a school shooting. Note, however, that no one in Washington is talking about highway deaths. Why is this?

The reason for the laser-like focus on an extremely rare phenomenon, however, is easy enough to explain. Many people genuinely believe—wrongly—that their children live in the shadow of school shootings. For gun control advocates, that’s all for the best, since this false narrative can be used to push more legislation.

Moreover, gun control advocates focus so much on school shootings because they contend—whether earnestly or cynically—that changing just a few laws will end school shootings. To believe such claims, however, we’d need to see some evidence not only that such laws reduce homicides overall, but that they also reduce homicides specific to schools. Secondly, these laws would have to work so well that they’d be worth the enormous costs to society—costs brought on by the drug war–like enforcement measures that such laws would entail. And in the meantime, far more widespread causes of child mortality won’t enjoy much attention in Washington because those awful things can’t be turned into a gun control campaign.

On the other hand, more practical and attainable solutions directly related to school security will be ignored.

School Shootings Are Incredibly Rare

Far from being a “norm” in American society, school shootings are a tiny subset of homicides which are themselves not exactly a leading cause of death in the United States. For example, there were approximately 16,700 homicides in the United States in 2019. That’s a rate of about five victims per 100,000 people. (By comparison, more than 100,000 Americans die of diabetes each year.)

Of those 16,700 homicides in 2019, 17 were due to shootings at K–12 schools. That means school shootings were 0.1 percent of all homicides and school-shooting deaths occurred at a rate of 0.005 per 100,000 Americans.

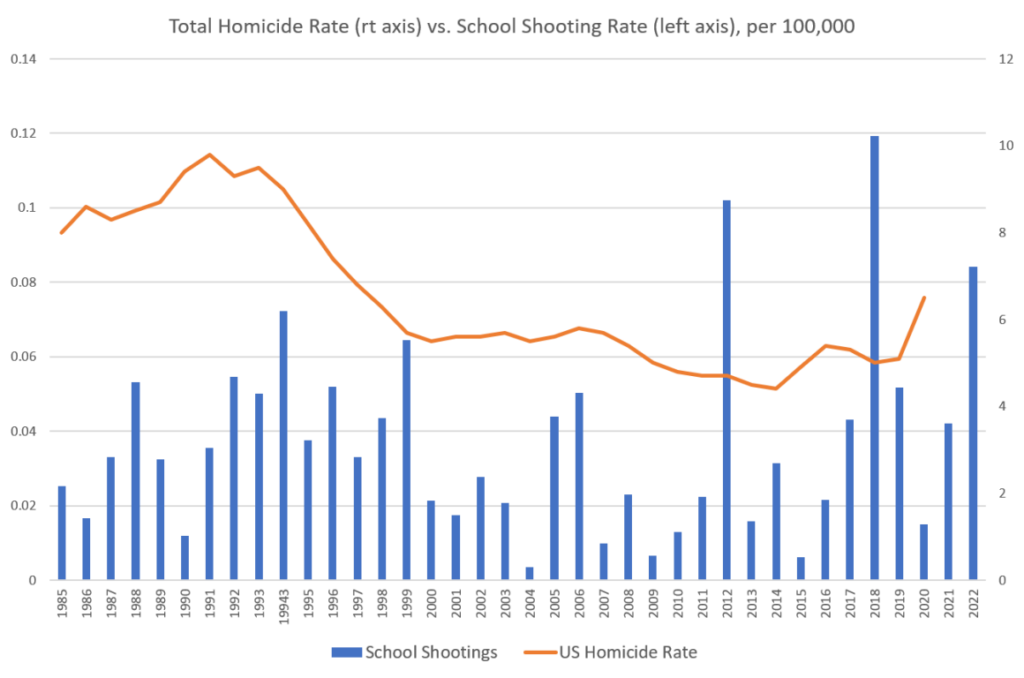

Some of the worst years for school shootings have placed homicides in the range of 20 to 30 deaths. Excluding 1927, the year of the Bath Consolidated School incident (which was a bombing rather than a shooting), 2018 was likely the deadliest year for schools, with 39 shooting victims. Twenty twelve—the year of the Sandy Hook shootings—was the second-deadliest year. Twenty twenty-two will likely be among the worst single years for school shootings, with at least 28 deaths.

If we look at school shooting deaths since 1985, we see that school shooting deaths per 100,000 swing from year to year—as we’d expect when total events are so few. In some periods, they can be fairly consistent, as from 1991 to 1999 (the nation in the early 1990s was emerging from a high-crime period during the 1980s). But consistency has not been the case over the past decade, with rates ranging from 0.006 per 100,000 in 2015 to 0.119 per 100,000 in 2018. These are small fractions of total homicide rates, and totals can change dramatically based on just one or two events.

Are the nation’s children in some kind of ghoulish shooting lottery? The data suggests policy makers should be far more concerned about children dying due to drunk-driving incidents, car accidents in general, suicide, drowning, cancer, or child abuse. Given the scarcity of the resources that can be devoted to addressing the dangers of the world, it only makes sense to put efforts toward those measures that are actually likely to save lives. In the worst years, we’re witnessing around thirty deaths due to school shootings. That’s 0.000009 percent of the American population. I’m not saying that’s something we shouldn’t care about at all. But it is an odd thing around which to craft national policy or to think should prompt national “soul searching.”

This raises an obvious question, then: Why are we not hearing about the urgent need to pass comprehensive federal anti–child abuse laws—or drunk-driving laws? It’s simple. Child abuse and drunk driving can’t easily be framed as something that requires the abolition of private gun ownership.

The focus is clearly on the passage of legislation, not the actual pursuit of safety. This is why advocates are not deterred when we find there isn’t much evidence that any of these measures actually bring down school shootings, or even homicide rates overall. Given that school shootings are so rare, it is virtually impossible to establish any sort of correlation between certain laws and school shooting rates, and we can of course point to cases that occurred in locations with strict gun control laws, like Sandy Hook. But even if we assume that a reduction of homicides overall correlates with less school shootings, can we be confident that stricter gun control leads to lower homicide rates?

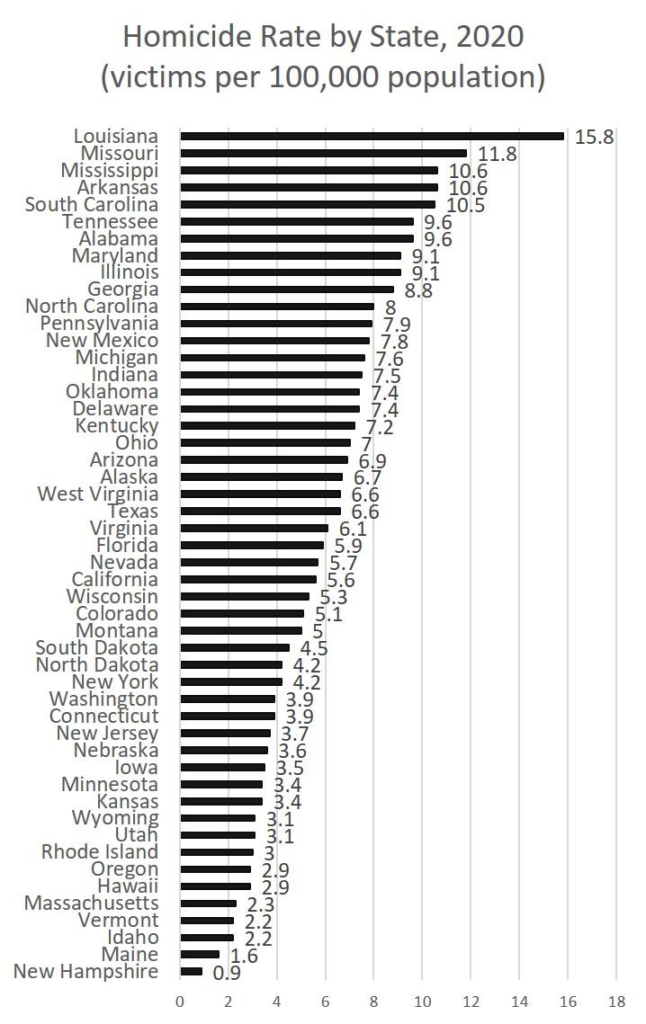

We can’t be confident in that regard either. After all, if we look to the Annual Gun Law Scorecard from the Giffords Law Center, we find that of the top ten states with the lowest homicide rates, only two states (Massachusetts and Hawaii) get an A– or better. Six of these states get a C– or worse (i.e., Vermont, Idaho, Utah, Wyoming, Maine, New Hampshire) for the strictness of their gun laws.

Basically, the gun control position is to introduce hugely broad legal measures requiring enforcement and depriving countless peaceful citizens of the human right that is private self-defense.

If addressing school violence is the real concern—and not just the headline grabber—the more practical solution is to address the security of schools specifically. Just as the private sector routinely employs security at its own facilities, schools need to be more targeted and practical in this regard as well. In any case, when addressing events that are as rare as school shootings, we’ll never have enough data to really know which measures deterred violence and which didn’t.

Read more:

- Public Schools Aren’t Taking Security Seriously

- Security Works at Disney—but Can’t Work at a Public School?

- Police Have No Duty to Protect You, Federal Court Affirms Yet Again

- Shootings: Why Don’t Schools Have Better Security?

- It Turns Out School Shooting Data Is Vastly Inflated

Originally published at Mises.org. Ryan McMaken is a senior editor at the Mises Institute. He has a bachelor’s degree in economics and a master’s degree in public policy and international relations from the University of Colorado. He was a housing economist for the State of Colorado. He is the author of Commie Cowboys: The Bourgeoisie and the Nation-State in the Western Genre.

Image source: Getty