Ryan McMaken – June 23, 2022

Here is an often-used tactic employed to defend government police organizations from criticism. Whenever critics point out police incompetence or abuse, defenders counter with: “The next time you need help, call a crack head!” This same phrase was used by Louisiana Senator John Kennedy when singing the praises of uniformed government bureaucrats in 2021. The phrase often produces many smug nods from the “Back the Blue” crowd, and one can buy T-shirts with this progovernment slogan as well.

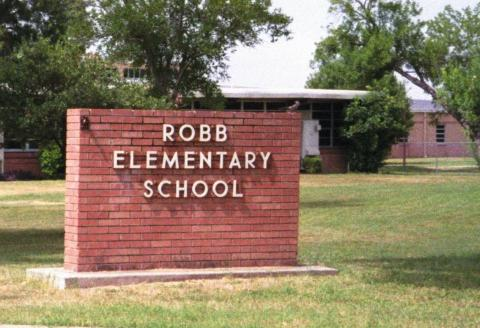

The reality however, is something quite different. Experience continues to teach us again and again, that when one encounters violent felons—as did the children in Uvalde, Texas—calling a crackhead may not produce results much worse than calling the police. A crack head is probably going to run the other direction when faced with a gun-toting maniac. As we learned at Uvalde, many police officers will do exactly the same.

The “call a crackhead” propaganda is also especially insidious because it is designed to back the idea that “taxes are the price we pay for civilization” and the myth of the “social contract.” In this supposed quid pro quo, the taxpayers pay their taxes, and then the government provides “public safety.” That, at least, is the myth the regime repeats over and over.

This myth is being exposed for what it is in real time in the Uvalde investigation right now. Each new revelation shows just how uninterested law enforcement officers can be in providing any of that “protection” they insist the taxpayers pay so much to fund. Rather, Uvalde has shown that the primary interest of law enforcement was officer safety, not public safety. So much for that “social contract” we keep hearing about.

Ultimately, unlike a private-sector service, police do not operate under any contractual obligations to provide services in any particular way. Thus, they can decide to do nothing and face no real consequences.

New Revelations Show Police Simply Chose to Do Nothing

In the Texas Senate this week, senators and the public are starting to see what passes for police work in Texas.

Although police spokesmen repeatedly claimed they could not engage the shooter because of a locked door, it turns out that was a lie. Reuters reported yesterday:

The classroom door in the Uvalde elementary school where 19 children and two teachers were killed in May was not locked even as police waited for a key, Texas Department of Public Safety Director Steven McCraw said on Tuesday.

There was no evidence any law enforcement officer ever tried the classroom door to see if it was locked, McCraw said at a Texas Senate hearing into the shooting.

“I don’t believe based on the information we have right now that door was ever secured,” McCraw said. “He (the shooter) didn’t have a key … and he couldn’t lock it from the inside.”

So, why did police wait outside so long? They claimed it was because they didn’t have the equipment they needed. That also turned out to be a lie. According to Steven McGraw at the Texas Department of Public Safety: “three minutes after the subject entered the building, there was a sufficient number of armed personnel to isolate distract and neutralize the subject…. the on-scene commander decided to place the lives of officers before the lives of children.”

Expect a Cover-Up

Naturally, police personnel and their allies in local government have acted to conceal information on the police response from the public. The city’s district attorney has intervened to prevent the release of “any records.” Moreover, the Texas Department of Public Safety is pressuring the state’s attorney general to ensure that body camera footage from the incident remains hidden—presumably forever because police rather conveniently claim the footage exposes police tactics to potential future shooters.

No Accountability

Unfortunately, legal recourse for police incompetence and inaction is virtually nonexistent in the US, and police have no legal or contractual obligation to protect anyone or do much of anything at all. Federal courts have made it clear police are simply not obligated to act to protect any member of the public. Police labor unions ensure police can easily deflect any legal woes related to “neglect of duty.” Additionally, the public is forced to pay for these non-services, diverting funds from potential private-sector services that would operate with clearly defined legal and contractual requirements.

In Texas specifically, little has been done to increase police accountability, such as making body camera footage more easily accessible. This has been done in some states such as Colorado. In Texas, however, police enjoy high political status and de facto political immunity from criticism. The routine solution for police issues in Texas is to hand more taxpayer money over to police. Police departments receive more taxpayer funding than anything else in Texas’s largest cities. Contrary to claims that police budgets are being bled dry by left-wing activists, Texas’s most left-wing city is increasing its police budget. The senate has passed legislation penalizing local governments that reduce police funding. The National Rifle Association’s only response to the Uvalde shooting has been to call for more taxpayer money for police.

Ridiculously, there is even a narrative that the police are among the victims of the Uvalde debacle. On the Joe Rogan Show, for example, retired US Army employee and author Tim Kennedy blamed Uvalde on the “defund the police campaign.” Kennedy argued police are subject to “demonization” and didn’t receive enough money to be properly trained. On Bill Maher’s Real Time, politician Michael Shellenberger said Americans should feel sorry for the police at Uvalde, mawkishly attempting to get the crowd on his side by stating “many of those police officers are having a hard time sleeping at night.” Shellenberger then went on to say it is wrong to criticize “our institutions” when “they fail us” and “the answer to it is more training.”

The truth is the Uvalde police, like most police departments, have received enormous amounts of funding and training on school shootings and related events. One training occurred in Uvalde just two months before the shooting. At the school on the day of the shooting, the police were better trained, better armed, and more numerous than the shooter. But when there is no system of legal or contractual obligations in place, we get a security force that relies purely on its own judgments at any given time.

But no amount of training can overcome the realities of police culture, which increasingly leans toward favoring “officer safety” over public safety. As Ryan Cooper has shown in The American Prospect, “American police are taught first and foremost to fear for their own lives” The lives of school children? That’s secondary. Cooper continues:

But this horrifying story should come as no surprise. What it illustrates is simply the cowardly culture of American police in action. Contrary to the chest-thumping rhetoric of police unions, they are neither trained nor legally expected to protect citizens in danger. In the pinch, they frequently put their own safety above those they are charged with protecting—even elementary school kids….

[The police response at Uvalde is] the polar opposite of approved police tactics these days. After the Columbine shooting, where police waited outside for hours while a teacher bled to death, police are supposed to dash into the scene as fast as possible. They just didn’t do it. The reason is the powerful fear instilled by other parts of police training, as well as the overall police culture.

That is, two important pillars of police training are at odds. On one hand, the training is to engage shooters. On the other hand, the training emphasizes that it is always a priority to ensure the police officer returns home safe. As explained by Ryan Grim, if this is the primary goal, the best tactic is to move more slowly to “reduce casualties”—namely, police casualties. The outcome is what we saw at Uvalde: police officers standing around waiting for more safety gear and more backup to ensure the police don’t get hurt.

Indeed, this attitude even broke through to the public when a Texas Department of Public Safety official Chris Olivarez admitted

if they proceeded any further not knowing where the suspect was at, they could’ve been shot, they could’ve been killed, and that gunman would have had an opportunity to kill other people inside that school.

In other words, the police had to protect themselves first, because if the police are hurt, then the suspect can do even more damage. There is a certain reasonable logic here of course, but it’s in conflict with post-Columbine training. Moreover, police know they will not be held to any contractual standard that mandates intervention. They can decide for themselves whether to intervene, and will face no consequences other than some short-term political blowback. Virtually no one in the Uvalde debacle has any reason to fear losing his generous taxpayer funded pension.

Moreover, the emphasis on officer safety may make police even less likely to put themselves in danger than an average person. After all, we frequently hear of good samaritans who put their own lives at risk to save children from drowning, traffic hazards, or other threats. Firemen rush into burning buildings to save people. These people have not been trained to focus on their own safety to the extent police have. Moreover, it’s a safe bet that many of the desperate parents at Uvalde would have rushed into [the school] to confront the killer themselves had they not been assaulted, cuffed, and tazed by law enforcement officers at the site.

Just the Latest Example

Any criticism of police will arouse claims that any reports of police shortcomings are just a matter of “a few bad apples.” Perhaps. But how do you know the local police in your town aren’t among those police officers who will let children die to avoid harm to themselves? Will you bet your child’s life on that?

After, all Uvalde certainly isn’t the only cautionary tale. Before Uvalde, at Parkland’s Stoneman Douglas High School, the police ran and hid while students were slaughtered inside.

The year before, it took police an hour and twelve minutes to respond to the 2017 Las Vegas shooter who killed more than fifty people as he opened fire on a crowd near the Las Vegas strip. Although hotel security had reported the location of the gunman—who had shot a security guard—even before the shooting began, local police agencies waited more than [an] hour before entering the shooter’s room. It remains unclear why the shooter stopped shooting after only about ten minutes, but we do know that he would have been free to keep shooting for a much, much longer period of time.

In contrast to this sort of police “efficiency”: in Arvada, Colorado, when a shooter opened fire in a crowded shopping district, the police ran for cover. The gunman was then shot dead by a private citizen with a gun. The police then came out of hiding and shot the good samaritan dead instead.

Private gun owners saved countless lives at a Texas church in 2019 where church members were the ones who shot back at the assailant, and then chased him down in a high-speed pursuit. The police did nothing but write some reports afterward.

Mere days after the police ran away in Uvalde, a woman in West Virginia saved lives by running toward danger to engage a gunman at a graduation party.

In other words, when your training emphasizes over and over and over again that getting home safe at night is of primary importance, how can we be surprised that police seem even less inclined to take on personal risk than the average Joe when it comes to saving children? So, when faced with danger, should we “call a crackhead”? Probably not, but if heroics are necessary, an ordinary person with a gun may be a safer bet than calling people whose primary concern is officer safety.

Originally published at Mises.org. Ryan McMaken is a senior editor at the Mises Institute. He has a bachelor’s degree in economics and a master’s degree in public policy and international relations from the University of Colorado. He was a housing economist for the State of Colorado. He is the author of Commie Cowboys: The Bourgeoisie and the Nation-State in the Western Genre.

Image source: Wikimedia