Ryan McMaken – December 20, 2018

Gun control advocates often point to Australia as an example of how “banning” guns leads to significant declines in homicide rates.

Whether or not the much vaunted gun laws were ever fully implemented remains a matter of debate, but data does indeed suggest Australia’s already-low homicide rates continued to slide downward in the twenty years following the alleged banning of guns.[1] Unfortunately, as Leah Libresco writes at the Washington Post, this doesn’t give us enough information to draw many conclusions:

I researched the strictly tightened gun laws in Britain and Australia and concluded that they didn’t prove much about what America’s policy should be. Neither nation experienced drops in mass shootings or other gun related-crime that could be attributed to their buybacks and bans. Mass shootings were too rare in Australia for their absence after the buyback program to be clear evidence of progress. And in both Australia and Britain, the gun restrictions had an ambiguous effect on other gun-related crimes or deaths…

That sample sizes should be so small in Australia is not a surprise. Commentators on Australia often neglect to note that the country has a population smaller than that of Texas. Obviously, the demographics, geography and history of the two regions are extremely different as well.

But with so few homicides to analyze in the first place, any asserted causality between the gun “ban” and homicide rates is indeed ambiguous.

Other data suggests that Australia’s experience is less than useful as an example to the rest of the globe. One of our readers, who goes by the pseudonym Alex Great, sent along a number of useful links in his own commentary which follows:

Proponents of gun control will point to the declining homicide rate and claim that Australia has seem zero mass shootings since the NFA was enacted.

However, analyses like this are quite simple and miss a lot of important data. For example, looking at official homicide data from the Australian government, we can see that the sharp decline occurred years after the NFA was enacted. A 2003 study backs this up, noting that homicide rates were already falling before the NFA.

A report from 2007 titled “Gun laws and sudden death: Did the Australian firearms legislation of 1996 make a difference?” also noted that homicides were already falling prior to the NFA being enacted, and found that the NFA did not speed up the declining rate of homicides in Australia. More recent studies still find that the decline in homicides can not be attributed to the NFA, since non firearm homicides also sharply declined in the same period:

There was a more rapid decline in firearm deaths between 1997 and 2013 compared with before 1997 but also a decline in total nonfirearm suicide and homicide deaths of a greater magnitude. Because of this, it is not possible to determine whether the change in firearm deaths can be attributed to the gun law reforms.

In fairness, a review of the literature from Harvard did find that states that had more guns bought back experienced more rapid declines in homicide. However, considering Australia was experiencing a decline in non firearm homicide at the same time, it is difficult to pinpoint exactly how much of an effect the NFA actually had. Even the review admits that no study was able to explain exactly why gun deaths were falling.

The claim that Australia has had no mass shootings since the NFA is also blatantly inaccurate, for example, there was a school shooting in Melbourne in 2002 that killed two and injured five. The 2014 Sydney Seige, where a man armed with a shotgun took a cafe hostage, also shows that despite the NFA, Australia has been unable to get rid of gun violence in public places.

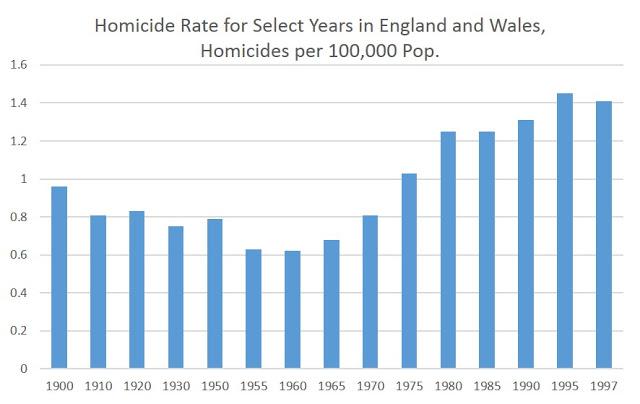

This lack of causality is also reminiscent of the gun control experience in Britain. As I noted in this article, England and Wales already had very low homicide rates — both historically and globally — by 1900. But given that gun control measures were not enacted until years later, it would be inaccurate to simply refer to gun control as the cause of low homicide rates in the region:

The first significant modern gun control law in the UK was the Firearms Act of 1920. The Act abolished what had been up until then an assumed right to carry arms. The Act was likely introduced as an anti-Irish and anti-communist measure, as there was no evidence (then or now) of rising crime at the time. The 1920 act was followed by increasingly restrictive gun control laws in 1937, 1968, and 1988. From the 1950s into the early 2000’s however, the homicide rate grew steadily.

Thus, these examples do not really provide a historical experience that we can point to and say “gun control led to low homicide rates in the UK and Australia.”

Footnotes:

[1] See also: “Media Reports Australians ‘Handed In’ 57,000 Guns Last Year; 37,000 of Them Essentially Handed Right Back” https://reason.com/blog/2018/03/01/media-reports-australians-handed-in-5700

This article was originally published at Mises.org. Ryan McMaken is a senior editor at the Mises Institute. Ryan has degrees in economics and political science from the University of Colorado, and was the economist for the Colorado Division of Housing from 2009 to 2014. He is the author of Commie Cowboys: The Bourgeoisie and the Nation-State in the Western Genre.